Table of Contents

ToggleTechnical Debts or how to ruin your code over time

Every coder involved in large projects has certainly heard this term at least once: technical debts. It's a term which doesn't sound special but it is quite an important one although neglected by even the largest projects. In general this term describes how software evolves. New features are added, existing ones modified and alongside the technology advances, coding standards change and coding languages change. This results in old code containing old ways of handling things which are not up to standard anymore from today's point of view. More often though corners had been cut in the past to reach dead lines or getting a feature working without actually getting it working correctly. Or sometimes you plain out didn't know all the tricks a coding language had to offer or certain requirements back at the time rendered these tricks not usable for the project.

Whatever the reason old code tends to pile up in projects which becomes hard to maintain, is error prone or even prevents new features to be implemented in a sane way. In the end technical debts pile up and should be removed from time to time to keep a project in a sane state. The problem here is the word "should". Let's be hones, no project lead, team lead or CEO of a company grants time to remove technical debts since this only costs time and money but yields no visible gain for the product. And if managers see no direct gain they allocate no time to do something. So the technical debts keep piling up until the project gets more and more problematic to work with. The large game engines around today all belong in the same category in that regard. Technical debts are not tackled since it looks better to pile more features on a flimsy undercarriage.

What goes for the Drag[en]gine game engine I know I had quite a bit of old code in the repository some of this code dating back to even before the game engine has been released to the public for the first time. I always wanted to get rid of some of the technical debts but never had time. I know tackling these would cost me many month to accomplish so I didn't tackle the work due to lack of man power at hand. But then Copilot came around and their coding AI agent actually turned into something you can actually work with. So I tried it out to see if using Copilot the massive amount of work could be reduced to a management amount for me to accomplish. And it turned out it is possible with a bit of preparation work and learning what the AI can do and where it falters quickly.

Copilot AI Coding Agent

Most of you certainly have heard the term Copilot yet, especially if you operate on GitHub. It is simply the name Microsoft gave to their AI system for development work. The Drag[en]gine is written in C++ and this is still the coding language with the most written code for it. It might be not as popular anymore as 10, 20 years ago but the amount of code already written using this coding language is huge so their AI had tons of free and open source projects to train on. Basically Copilot splits into two functions: inline editing and AI agent.

Inline editing is what most people more or less voluntarily used so far. If you use something like Visual Studio Code then Copilot provides code completion results while you type. At the beginning this looks crude but after Copilot gets to know your project better the suggestions are actually quite right. As always AI generated code has to be verified but with inline editing often only a bunch of lines of code are generated which you can quickly check while typing. This feature really does speed up working and reduces typing errors.

The AI agent though is something many do not have on their radar. This one is more tricky to use and it exists in a VSCode internal version and one running on GitHub coordinated usually through the web browser. I started out with the GitHub remote version when testing if the AI agent is usable for this huge refactoring task. While it does work it is tricky to work with. The main reason is that the GitHub agent creates a new feature branch (which is a good thing) but then keeps on committing various work steps along the way. This causes the repository history to bloat a lot since the AI (especially in the beginning) like to make mistakes which then have to be fixed with reverting commits or modifying commits. If you go that route you should do (after the work is done) a pull request with squashing commits. This collapses all the changes into a single commit to merge into the main branch dropping the large amount of commits the AI agent coughed up. The hard thing on this solution is that you can only do reviews on pull requests. It is hard to adjust the code produced by the AI and throughout all this refactoring it showed that AI agent generated code always has to be fixed in smaller or larger amount to be usable. But with reviewing pull requests this is not possible. And that's where the second mode comes into play.

The second mode works inside VSCode using what the call MCP agents. If you open the chat prompt window you have at the bottom left a combo box.

By default this one is set to "Ask". But interesting here is the mode "Agent". This allows to run a coding agent on GitHub but with access to the workspace files and state inside VSCode while controlled from the chat window. You can also set the AI model to use. In my tests only "Claude Sonnet 4.5" produced results which are useful. Don't use "Auto" as this will switch between models between prompts. This causes problems with variable quality of generated code and since different models produce different results they tend to get upset seeing code from other models while doing their work. The nice thing on this setup is that changes made by the AI show up as regular edits in the Git panel. This allows to easily verify what changes the AI made and to adjust/fix the changes to be committed the way you want it to be committed. The AI agent runs slower than the one on GitHub only but since you can directly modify the generated edits you are in the end much faster without needing to deal with commit drama.

No matter if you use the GitHub AI agent or the VSCode controlled AI agent there is one thing that is useful: creating a copilot instruction file. I've linked the one used in the Drag[en]gine repository. Basically this file is read by Copilot AI agent (both GitHub remote or VSCode local) before doing any work. It can be used to write down rules for the AI to follow. These rules can be anything from coding style to does and donts or even code samples on how you want certain type of code to look like. In general the AI agent replicates your coding style so that's usually not much of a problem. But this file is especially useful to tell the AI to never touch certain files. For example in the Drag[en]gine repository external code (like libpng for example) is present in the extern directory. In some situations foreign code is present inside the source directory (for example Bullet Physics Library). In all these situations you do not want the AI to modify or even consider these foreign files. Using the copilot instruction file you can tell the AI to totally ignore such files which is a great help. So if you plan on using Copilot AI agent creating that instruction file is one of the first things you should do as it will make your life so much easier and results so much more usable.

For the entire refactoring I used this setup successfully.

Let the battle begin: Refactoring

Let's start first with some raw numbers before diving into what has been done:

- Refactoring team: Me + Copilot AI

- Refactoring time: Roughly 7 weeks (including learning time how to use AI refactoring most efficient)

- 11'330 files changed (~230 per day)

- 460'857 lines inserted (~9'400 per day)

- 682'145 lines deleted (~14'000 per day)

You can see here the code got significantly smaller which is one of the benefits from the refactoring. Less moving parts means less potential for bugs or problems. So what has been done in particular over all this time?

Memory Management

The biggest work by far has been replacing old memory management with modern concepts. The base code used in the game engine existed already before the Drag[en]gine has been officially born as project and made available to the public. Back in those times things like C++ templates had been still an unsafe thing to use since different compilers had conflicting ideas on how to implement it and templates in shared libraries had been problematic to use. For that reason manual memory management had been used with a bunch of list and dictionary classes without templating to simplify the work load. As the project grew these manual memory management and list/dictionary classes got copy pasted around and ended up everywhere in the project. This had not been to my liking but getting this out of a project clocking in at over half a million lines of code had not been a feasible thing to do up to now. So I went ahead to refactor the biggest trouble points across the entire code base.

All the manual list and dictionary management class (like deObjectList) have been replaced with a small set of template based collection classes. Why not using stuff like std::vector? While generic the standard library container classes and algorithms have one particular weakness, and these are iterators. Iterators are a great concept for generic programming but due to their nature they cause horrendous code bloat. Since you always need a begin and end iterator for every algorithm you have to use lots of temporary lists stored in code. Storing temporary results as variables in code though allows for accidentally using them later on potentially causing subtle bugs sooner or later. Furthermore these collection classes have inconsistent behavior on their functions/operators so you can easily do an unchecked index look-up causing strange crashes. I wanted all the common operations needed often in the game engine to be compact and with as little local variables as possible to make the code easier to understand and to minimize errors. With this I can do now code like this example:

projects.Collect([&](const Project &project){

return project.GetName().FindString(namePart) != -1;

}).Sort([](const Project &a, const Project &b){

return a.GetName().Compare(b.GetName());

}).Visit([&](const Project &project){

// do something with project

});

There are various functions in these collection classes to be used like this: Visit(), VisitIndexed(), Find(), FindOrDefault(), Collect(), Inject(), Fold(), RemoveIf() and so forth as well as ranged overloads of them where useful. While all doable with standard library this is much smaller in code lines and thus easier to understand what is going on and no temporary variables lingering around potentially blowing up code.

Another something is how containers like std::vector manage memory especially in connection with reference templates. This can quickly become inefficient in something like a game engine. With these template classes I've designed the memory model in a way I get the performance and convenience I need without sacrificing one or the other.

With this I refactored now all old collection classes (like deObjectList, dePointerList, deIntList) with template collections which now also have a unified API (the old ones had not been unified unfortunately). I also refactored all manual memory managed for ** arrays, * arrays, dictionaries and linked lists with the new template collections. This unifies the code, avoids bug sources and heavily reduced code.

Since these template collection classes are so vital and heavily used across the entire code base I also let the Copilot AI add a set of comprehensive tests to the existing game engine tests. We all (coders) hate doing two things: documentation and tests. With the AI mustering up tests (and me reviewing them) this process had been cut down in time a lot and makes "add tests" more likely to happen. Manually created tests certainly can catch more corner cases but any function tested is a potential bug avoided. So the generated tests helped a lot.

Another something I've added is deTUniqueReference. As the name suggests it is something similar to std::unique_ptr but implemented with a similar API than deTObjectReference. What's wrong with std::shared_ptr and std::unique_ptr? Actually a couple of things and all of them more or less big problems. First of all both of these cause abort() if a null-pointer is dereferenced. Hence if you do a small mistake and you dereference a null-pointer the entire game or editor just plain out crashes hard. This is not what I want to happen. Instead I want an exception to be thrown which can be caught and handled in a sane way. The second problem is that std::unique_ptr does not work well with classes containing virtual methods (aka virtual classes). But this is something I really want to do hence deTUniqueReference is working together with virtual classes as one expects them to.

All in all I have now a sane template based memory management system which provides in-class methods for often used algorithms without littering your code with temporary variables. That's the way to go forward and spending this extra time to clean up this huge technical debt has been worthwhile.

Bug Fixing “on the go”

While refactoring I stumbled also across various bugs that went unnoticed in the old code but which surfaced with the new template collection based code. This is actually a good thing but also caused the refactoring to take longer.

I also tackled some TODOs which went dormant in particular in the editor. I'll tackle more of those TODOs in due time but for now that has been fixed is fixed and the rest will be done when it's done.

The Good, The Bad and the Ugly

During the refactoring I also came across one of the most annoying problems I had faced in a long time and I would like to gives this problem an extra section here since others might trip about it too. But first things first.

Last December I did the regular updates on Visual Studio on the Windows development machine. This is where the Windows compilation and testing of the Drag[en]gine is done to make sure it works also on this system (which is The Bad" and "The Ugly" at the same time). Around that time Microsoft did a large update of Visual Studio replacing the 2022 version with the new 2026 version. I'm sticking to 2022 for compatibility with GitHub build work flow and other reasons. Still the compiler in Visual Studio 2022 also got updated. So I recompiled the game engine to test things and then something strange happened. The editor worked but running any kind of game with the game engine made it immediately crash with no useful exception at all. The debugger also did not manage to show any reason for the crash. I've been stumped. What the hell is going on here? The compiler update must have broken something but what? After a lengthy debugging and problem searching with googling around a lot I stumbled across a strange Heap Access Violation problem. I didn't sound plausible at first but I then dug a bit deeper into the search results.

Basically a class of type T gets a function F called but instead of calling it on T it got called on some other unrelated class X.

Obviously if X::F() is called instead of T::F() then you get all kinds of nasty segfaults. But how is this possible? If you have pointer of type T* you call F on how the hell can this function be called on X instead? The answer had been both "Bad" and "Ugly". But let's take a step back first to the where it happens.

In the game engine I use DragonScript script language which is based on on a language I wrote back in University. What student does not write a smaller or larger language after attending the obligatory compiler courses at university. In contrary to other script language DS is based on the concept of native script classes. This allows C++ based code to easily embed DS scripting by providing native script classes fusing script code with C++ code in a sane way (hence no c-call bridges). To achieve this native script classes can request a certain amount of data to be reserved when creating a new object of said script class. This uses malloc() to allocate and free() to release the memory. CPUs though have alignment requirements. Basically 4 bytes (DWORD) alignment is necessary but 8 bytes is safer (sizeof(void*)). Hence the native class data is aligned to 8-bytes which worked without a problem so far on Linux, Windows, Android and other systems.

But now suddenly this did not work anymore, but only on Windows, and only on the new compiler. So what happened?

The answer is that the compiler became more aggressive in optimizing generated machine code. So why should this be a problem? Is the alignment not enough suddenly?

The answer is "no... except". An alignment of 8 bytes is fine on Windows. This is not causing a problem. If you use though a "over-sized" struct, hence a struct containing an 128 wide member, then the alignment requirement can jump to 16 bytes. I do not use anywhere 128 wide members in native class data so that's not the problem. Still Windows can potentially crank up this requirement silently and without warning so if you want to be 100% sure to never run into head alignment problems use this code:

// For std::max_align_t

#include <cstddef>

// Align to at least 16 bytes on Windows to prevent SIMD crashes.

template<typename T>

consteval size_t AllocAlignment(){

// std::max_align_t is often 16 on modern Windows/Linux to support x64 SIMD.

return (alignof(T) > alignof(std::max_align_t)) ? alignof(T) : alignof(std::max_align_t);

}

// Alignment offset for memory received by malloc() or libraries where you do not know how the memory has been allocated

template<typename T>

inline T* AlignAlloc(void *buffer){

const uintptr_t addr = reinterpret_cast<uintptr_t>(buffer);

constexpr size_t align = AllocAlignment<T>();

const uintptr_t alignedAddr = (addr + (align - 1)) & ~(align - 1);

return reinterpret_cast<T*>(alignedAddr);

}

So this way the alignment is now 16 bytes to be on the safe side for Windows. On Linux 8 bytes is fully fine.

Now this bloats the memory somewhat since now native data is aligned to 16 bytes to be on the safe side instead 8 bytes. 8 Bytes wasted... because of Windows. Great, just great! It can't get worse than this, right? Right?! Well, we had now the "Bad" but now comes the "Ugly": It still crashed. But why? We had been now super conservative while aligning the allocated memory. Why still crashing?

The answer is again in the more aggressive MSVC compiler update. And this problem is subtle but devastating. You might have noticed I highlighted above the word head alignment. That's because MSVC requires also "tail alignment".

Usually you do not get in touch with tail alignment since it happens automatically. If you have a struct like this:

struct MyStruct{

uint64_t a; // 8 bytes long

uint8_t b; // 1 bytes long

uint64_t c; // 8 bytes long

};

then you have head alignment of 7 bytes on c so it falls again on the right memory location. But this head alignment is also implicitly the tail alignment of b. So far nothing special. We aligned each member to fall on the required boundary so where's the problem?

The problem is MSVCs agressive optimization (the "Ugly").

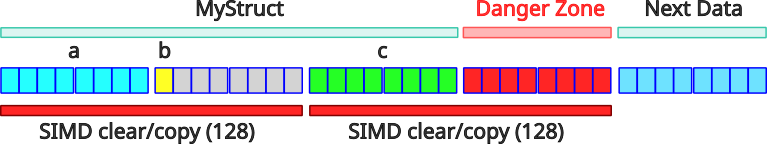

In the example above your struct is aligned to 8 bytes since c is aligned to 8 bytes and has a size of 8 bytes. When clearing the memory, for example during a placement new or due to an operator=(), MSVC does now no more clear the memory as you would expect. Clearing this memory it makes sense to clear only the 24 bytes covered by the struct members. The padding between b and c can be fill with anything as it is not used. So what can go wrong? With the optimization upgrade MSVC now tries to use SIMD instructions to clear/copy the memory as fast as possible. But SIMD instructions are 128 in size. Hence MSVC tries to clear/copy now the memory using two 128 SIMD clears, which totals up to 32 bytes. You see already where this is heading to? MSVC now clears/copies 8 bytes past the last member of the struct.

Hence although the struct is 24 bytes in size the upgrade MSVC now clears 32 bytes. With other words MSVC will overwrite the 8 bytes of the following data in memory!

The annoying part is that this overwriting of data is not considered a heap violation by Windows but accessing the trashed memory sure is!

And this had been what caused me all these problems. After the native data the next class pointers had been located and MSVC went ahead and happy-go-lucky trashed the next 8 bytes causing all kinds of troubles.

So what happens here? MSVC now requires your data to not only be head aligned it also has to be tail aligned!

What does this mean? The struct is 24 bytes long. If you make the next data adjoin the struct directly Linux, Android, GCC and Clang all are happy with you but MSVC is going to punish you by silently overwriting 8 bytes of the next struct with it's aggressive SIMD clear instruction. The solution for this problem is to add tail padding. You have to artificially blow up the size of your struct to protect yourself against MSVC. The following code does this:

template<typename T>

consteval size_t AllocSize(){

return sizeof(T) + (AllocAlignment<T>() - 1);

}

This function tells you how much memory to "really" allocated to not fall into this trap. Hence sizeof(MyStruct) is 24 but AllocSize<MySize>() is 32. You have to reserve 32 bytes or your can get bitten by MSVC.

Now this all applies if you are required to manually manage memory, for example by using memory pools or other techniques. You can always use the allocation alignment function from earlier for all your data but this will introduce a lot of padding blowing up your memory consumption. For example for a struct of 1 byte size you correctly need to allocate 31 bytes of memory. That's correct. If you get malloc() memory you have to head align it by up to 15 bytes and tail align it by up to 15 bytes to be on the safe side. Hence 1 byte + 15 bytes + 15 bytes = 31 bytes to allocate for a single byte to be on the safe side. Good thing is it is not that bad in reality.

- When allocating the pool memory align it using the earlier function. You have now the head alignment covered.

- Inside the pool ensure to enlarge the memory size of structs by using

AllocSize<T>()to get the correct stride. This covers the tail alignment.

In this situation you loose up to 15 bytes on allocating the pool memory (head alignment) but only up to 15 bytes instead of 30 for each struct inside the pool.

This situation cost me some time until I figured out why the new MSVC compiler killed me. And all this because MSVC aggressively uses SIMD 128 clear/copy instructions without wasting a single though about writing past the struct size. That's the Bad and the Ugly. Let's be happy Linux/Android/GCC/Clang is the good.

I hope I could spare you some debug time when things suddenly fail on your when you upgrade MSVC.